Spanish-American

Institute

English-in-Context:

Teaching English in

Computer Education

III. Principles of Good Teaching

IV. Learning English In Real World Computing

Contexts

VI. Assessing Independent Projects

VIII. Faculty Requests for Instructional

Support

rev. 08/31/11; 05/24/10; 10/20/09

English-in-Context: Teaching English in Computer Education is the new title for the former Spanish-American

Institute publication, Computer Teacher Orientation:

Integrating Language Skills in Computer Education. While the two texts are essentially the same, the new title

better reflects the principles underlying the English language learning

purposes for offering non-ESL courses to ESL learners.

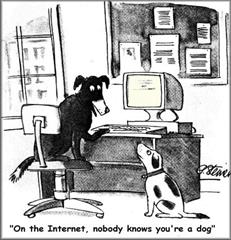

Each and every course at the Institute is a language

learning class. The only difference between ESL and

non-ESL classes is that ESL classes teach English through conventional ESL

materials and practices whereas non-ESL classes teach English in context, in

this case the context of computer applications.

Teachers and students are

expected:

Š

to use only

English language in exploring computer applications and

Š

to integrate the

four language skills (reading, writing, listening, and speaking) in their work

on a daily basis.

Bound copies of the

Institute’s course syllabi are available in the Computer Room, in the Student

Room, in the Library, and in other strategic locations throughout the school as

well as on the school website.

Noisy students are certainly

not learning very much. However,

quiet students are not necessarily learning much either. Because a student does not ask a

question does not mean that the student understands. Good teaching means

actively interacting with individual students each class session to assess that

they:

- understand what is expected of them and

- can explain orally and in writing how they have

approached the targeted skill.

To help students learn,

question each student each class about what he or she is doing or has done to

determine any need for additional help. Doing so helps students develop

critical English language skills through the targeted computer skills within

real world contexts.

III. Principles of Good Teaching

Computer-based teaching

shares principles of good teaching common to all disciplines. These include:

1. Respect

for Students. Good teachers assume that

students are mature, intelligent people who have something to say, even when

not fluent in English.

1. Respect

for Students. Good teachers assume that

students are mature, intelligent people who have something to say, even when

not fluent in English.

2. Critical

Thinking/Higher Order Thinking Skills. "Thinking" with a

language develops neural pathways in the brain. When students think with or create with

language, they begin to make it their own because thinking imprints language

patterns in their brains. The same is true of learning any

computer skill. Students have not

“learned” a skill until they have made its patterns and applications their own

by using it in a variety of ways, including talking, reading, and writing about

it.

2. Critical

Thinking/Higher Order Thinking Skills. "Thinking" with a

language develops neural pathways in the brain. When students think with or create with

language, they begin to make it their own because thinking imprints language

patterns in their brains. The same is true of learning any

computer skill. Students have not

“learned” a skill until they have made its patterns and applications their own

by using it in a variety of ways, including talking, reading, and writing about

it.

3. Vocabulary Learned From Context. When teachers encourage them to do so instead of giving them the

answers, most students can figure out the meaning of most words in computer

texts from context. This reinforces

an important facet of language learning, inferring meaning from context.

4. Grammar Learned From Context.

Students also

learn grammar from context through practice in reading, writing, speaking, etc.

Only through practice in using the language does the he grammar of

any language becomes embedded in the brain, ready to be understood and applied

to new situations.

5. Active

Learning “Safety Nets.” Good teaching starts with structured activities in which students can

practice specific skills, including language skills, without feeling

threatened. Good teaching provides

students with “safety nets” that ask students to do only what they have previously

learned.

Most learning is cumulative.

Good teaching means never asking students to do anything for which they

have not been prepared through progressively more challenging cumulative

activities.

- Student Questions Are Teachable Moments. No

question

is a dumb question. However, the

teacher should rarely provide the answer.

In student-centered learning, consider questions a teachable moment, an

opportunity to guide them through the learning process involved in working

through the answer themselves.

7. Facilitating (Not Giving)

Answers. Instead of

providing the answers, good teachers help students

find them by questioning them further, step-by-step if necessary. This active approach to teaching will

not only help students better develop language and critical thinking skills but

also help them learn the target computer-based skill.

Another

tip: If students do not know how to

perform a task in the way the textbooks requires, ask them if they know another

way to do it. That will challenge them

to think more about the problem.

After they have tried “their” way, have them go back and do it the

book’s way.

IV. Learning

English In Real World Computing Contexts

The Spanish-American

Institute uses instructional materials in all its computer-based courses that

help teachers to:

Š

develop students’

English as well as computer skills and

Š

incorporate the

principles of good active teaching practice above.

V. The DDC Model

Where available and current,

the Institute uses the DDC series in computer applications courses.

The DDC series provides an

excellent model of active teaching and learning that teachers can use to

strengthen students’ English in computer contexts. Teachers can adapt the DDC model of good

teaching to computer-based courses that use titles not in the DDS series as

well.

Each DDC lesson contains real-world

background reading and activities that move students from simple English and

computer skills acquisition to more independent application of these skills “on

their own.”

DDC textbooks call units or

chapters Lessons. Each Lesson is

divided into several Exercises using several different learning modalities and

multiple activities. Think

of Lessons as chapters and Exercises as sequential, cumulative learning

activities.

The DDC material helps

teachers to seamlessly integrate language and computer skills using the

following activities.

1. “Skills Covered.” Each

Exercise begins with a list of terms that will be used throughout the Lesson to

describe the target skills.

Using “Skills Covered” For English Language Learning. Reassure students that they do not

need to understand every word or term used in this list to begin with. However, make them understand that by

the end of each Exercise they should be able to both explain in English and to

apply each of the “skills” listed.

2.

“On The Job.” Each

Exercise starts with two brief “On the Job” readings that

provide the real-world

context for student learning.

The first reading describes

how certain target skills may be used in general job situations. It uses terms and vocabulary about

computer skills learned in the previous chapter(s).

The second reading directs

students to think about how these applications might be applied to a specific

job situation. The specific job

situation provides the working context for the student’s succeeding work in the

Exercise

Using “On the Job” For English Language Learning. Go

over the reading passages with students, asking them questions about the

readings to see how well they understand them.

If students do not understand

the vocabulary or context of the readings, it is more than likely that they

have not mastered the skills and vocabulary of the preceding Exercise(s). In this case, return students to the

preceding work. Depending on the

situation, ask students to repeat some or all of the preceding work and/or

coach them to explain it in English as best they can.

3. “Terms.” “Terms” contains definitions of key

words at the start of each Exercise.

These terms are highlighted in the text. If students do not understand terms

highlighted in the text, consider this a teachable moment.

Using “Terms” To Integrate English

and Computer Learning.

Instead of explaining the term to students, make them go through the learning

process themselves by referring them back to “Terms” and asking them to explain

them in their own words.

4. “Notes.” “Notes” describe and outline the

computer concepts in each Exercise.

5. “Procedures.” “ Procedures” provide hands-on mouse and keyboard practice that teach

the target skills. “Procedures” are

always written as directions in the imperative form of the verb (e.g., do

this, do that).

Using “Procedures” For English Language Learning. Teachers

should encourage students to talk about what they are doing, will be doing, or

have done in this section. This

interchange will give students practice in change from the imperative form of

the verb used in the text to the present, future, or past tense.

6. “Application Exercise/Exercise Directions.” The

“Application Exercise” provides step-by-step instructions putting the target

skill to work.

Using” Application Exercises” For English Language Learning See 5, above.

7. “On Your Own.” “On Your

Own” is perhaps the most important part of the textbook. It provides a critical thinking

opportunity that challenges students to apply what they have learned to

particular problems. DO NOT LET STUDENTS SKIP THIS SECTION!

Using “On Your Own” For English Language Learning. Never

allow students to skip this activity.

Instead, use it to assess student mastery of the targeted skills through

the use of English language reading, writing, listening, and speaking. For example, ask students to write out

their approach to the activity and to explain it orally, step by

step. Also ask them to discuss

their approach with one or more other students. If they have not adequately completed

this independent learning task, ask them to repeat earlier learning activities

to assure skills mastery before returning to “On Your Own.” AGAIN,

DO NOT LET STUDENTS SKIP THIS SECTION!

MAXIMIZE THE POTENTIAL OF THIS SECTION TO REINFORCE ENGLISH LANGUAGE

LEARNING THROUGH APPLICATION TO COMPUTER CONTEXTS!

8. “Critical

Thinking Exercise.” To complete this task, students must

have mastered the target computer and language skills. Like “On Your Own,” use this activity to

assess student language and computer learning and, if needed, return

students to previous work. AGAIN, MAXIMIZE THE POTENTIAL OF THIS

SECTION TO REINFORCE ENGLISH LANGUAGE LEARNING THROUGH APPLICATION TO COMPUTER

CONTEXTS!

Using “Critical Thinking Exercises” For English Language

Learning. See “On Your Own, above.

VI. Assessing Independent Projects

Most computer-based course

syllabi ask students to demonstrate that they have mastered the course’s

learning objectives through independent projects such as those found in their

textbooks.

Structure these projects so

that students demonstrate language as well as computer skills. For example, ask students to:

Š

write a summary

of the project,

Š

list the steps

that they took to carry out the project,

Š

state the

computer skills that they needed to carry out the project,

Š

discuss the

challenges they faced in undertaking the project, and

Š

where feasible,

present the outcomes of their project before an audience.

VII. Good Testing Practices

The Institute expects

teachers to follow good testing practices in developing bi-monthly and other

exams. Check if exams.

The most important testing

practice is to test English skills through the balanced distributions of

testing questions that require:

Š

reading (whole

passages, not only sentences),

Š

writing (shorter

and longer answers),

Š

listening (where

feasible), and

Š

speaking (through

presentations and/or one-on-one oral questioning by faculty).

In addition, tests should:

Š

correlate to the

textbook and other teaching material.

Š

make use of

publishers’ testing materials, if any, as well as any additional material you

have developed.

Š

reflect

principles of good practice and up-to-date teaching methods

Avoid questionable testing

practices like the following:

1. Avoid

Passive Testing. For example, do not ask students to define

terms. Instead, ask them to apply

the term or concept in a problem.

2. Avoid

Fill-in-the-Blanks and Multiple Choice Testing. Tests should rarely if ever ask students to

complete sentences by filling in the blanks or to pick a multiple choice

answer. Test questions should

involve reading comprehension, language comprehension, and computer based

skills applications.

3. Avoid

Testing at Too Low or Too High a Level. Tests should challenge students to create at a level

consistent with their time spent in the computer-based class and their ESL

placement.

VIII. Faculty Requests for Instructional

Support

Faculty Requests for Instructional Support. The

Institute encourages faculty to request other courseware, print material, and/or

memberships that help them implement the curriculum and Institute learning

objectives.